This work is a translated, revised, and updated version of subsections 2.1.1 and 2.1.2 of my master’s dissertation (Carvalho, 2023). These subsections provide a brief historical overview and classification of the approaches found in the field of Computer Science Education. The present translation was prepared during the application process for the Certificate Scholarship at the New Centre for Research & Practice, in the Transdisciplinary Studies program.

Carvalho, W. R. B. (2023). EMPADARIA - framework para o desenvolvimento de ficções interativas por meio da Pedagogia de Projetos. Dissertation (Master’s in Computer Science) - UFABC (Universidade Federal do ABC). São Paulo. Link

Approaches to Computer Science in Education

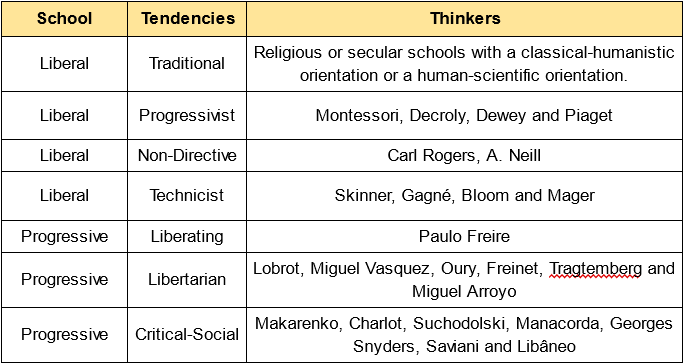

Established over 50 years ago, the field of computer science education (CSEd) encounters a diversity of references, knowledge, and practices from the groups that compose it. This section highlights the efforts by these groups, contributing to the intention of situating the current work in the current CSEd scenario. Table 1 presents a classification proposed by Libâneo (2009) of pedagogical trends that underlie the CSEd approaches discussed in the next section.

Table 1 - Pedagogical trends (from Libâneo, 2009)

There are various approaches to classify actors in CSEd, whether through their differentiated historical context, tools, pedagogical objectives, learning theory, or the combination of two or more factors. Valente (1989) identifies more than one interpretation for the term “educational software” from different groups: (I) computer-assisted instruction (CAI), (II) discovery learning tools, and (III) tools with educational potential for both students and educators. They differ in their software specifications and educational potential. When one of the three meanings is used, we can identify the alignment with a particular pedagogical trend or a hybrid pedagogical approach.

Actors in CSed

Among the possible classifications to contextualize CSEd in Brazil and worldwide, Neto (2002) proposes a classification based on five historical moments, mainly stemming from the possibilities and limitations of the type of technology available in each period, with the following ‘waves’: (1) administrative, marked by the first computers; (2) Logo language and programming, marked by computers like Hotbits and MSX; (3) Basic Informatics, marked by the graphical interface; (4) educational software, marked by the development and consumption of software in educational conglomerates; and (5) Internet, Information, and Communication, marked by the advent of the internet and its developments.

Kaminski, Klüber and Boscarioli (2021) propose a classification of CSEd projects in the history of Brazil based on the pedagogical trends defined by Libâneo (2009), considering different historical periods, the impact on basic education, the guiding epistemological axis, and the generational classification of teachers and students. Another popular classification in the literature is proposed by Papert (1993), identifying two major approaches to IE, namely the instructivist approach and the constructionist approach (Almeida, 2000). The instructivist approach is based on Skinner’s theory, related to Radical Behaviorism thinking. His idea of programmed instruction is marked by the ideal of enhancing performance in activities through more efficient individual technologies, or “teaching machines” (Teles, 2018; Aguiar, 2020).

The first computer projects in the United States were seen by behaviorist researchers as opportunities to apply Skinner’s programmed instruction through the use of interactive media in various disciplines. This inaugurates the instructivist approach through the articulation of experimental psychologists from the radical behaviorist line with experts from different areas, such as instructional design, audiovisual education, mathematics, and systems engineering (Dick, 1965; Seels, 1989). In this approach, learning occurs through the memorization and reproduction of content, focusing on ensuring the transmission of knowledge, as observed in the instructional design present in courses and CAIs (Neves et al., 2012).

CAIs can be defined as software that, as finished products, can use tutorials, quizzes, educational games, or simulations to instruct students in specific knowledge in classrooms (Almeida, 2000; Tarouco, 2019). The main criticism is the passive position given to the student in the educational process, as learning occurs solely through processes of repetition and memorization (Chaves et al., 1983). Variations of this type of educational software exist, such as Intelligent Computer-Assisted Instruction (ICAI), which reproduces the behaviorist discourses with the help of artificial intelligence in the construction of individualized teaching situations (Almeida, 2000).

In the academic environment, the instructivist approach has accompanied technological advances over the last 30 years, refining and validating the techniques and instruments used by its members, as well as proposing and finding new spaces for reproduction, such as Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs) and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) (Garrido et al., 2020). Additionally, from the 2000s onwards, there is the emergence of courses structured by technology companies, such as Code.org and Microsoft using instructional design techniques to popularize computer science and increase the availability of labor in the market, as observed by Kafai, Proctor and Lui (2020).

This represents an alternative manifestation of the instructivist approach, based on similar instructivists assumptions present in the academy but for different reasons, since its educational proposal is aimed at the skills defined by tech companies (Aguiar, 2020). This approach inaugurated by the is represented in the document ‘Standards for Computing in Basic Education - Complement to the National Common Curricular Base’ (BNCC) with the name ‘Market Demand’ (Brasil, 2022), based on the classification proposed by Raabe, Couto and Blikstein (2020).

The constructionist approach is inaugurated by Papert, with an understanding that computers should be used as educational tools in solving significant problems, so that knowledge is constructed from students’ own actions. An important characteristic of constructionism is the emphasis on the realization of knowledge through reflection in the process of formalizing ideas and models into mental creations and physical representations (Papert, 1993; Almeida, 2000). His thinking was inspired by ideas from Dewey, Freire, Piaget, and Vygotsky (Almeida, 2000). It is presented in the Complement to the BNCC as a second approach titled ‘constructionism’ (Brasil, 2022).

In order to provide autonomy in the student’s learning process, Papert introduced the Logo, which enables the development of computational thinking through discovery by students as they explore the diversity of possibilities in the tool (Almeida, 2000; Santos & Mafra, 2018). Logo stood out from the languages of its time for its simplicity in the way students express themselves through commands, based on data structuring, initially designed to assist in learning mathematics (Papert, 1993; Almeida, 2000). Other technologies can operate in the same approach of offering autonomy to the student and enabling the educator to understand the student’s cognitive style. Examples include text production tools, such as PhET and Scratch (Santos, 2018). Ayala and Yano (1998) presents a classification similar to Papert’s but structured sequentially, with constructionism as a response to the instructivist approach, followed by computer-supported collaborative learning based on Vygotsky’s learning theory.

A third and fourth approach are identified by Raabe, Couto and Blikstein (2020), presented in the document ‘Standards and Complement to the BNCC,’ titled ‘Computational Thinking’ and ‘Equity and Inclusion,’ approaches originated by the Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA) (Brasil, 2022). Different authors attribute the emergence of the Computational Thinking approach to Jeannette Wing’s article ‘Computational thinking’ (Wing, 2006). Despite this, it is possible to identify this idea in curricular debates for higher education by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) such as the ‘Computing Curricula 1991’ (ACM/IEEE-CS, 1991). This context guided the formation of a working group for the composition of a curriculum for high school students in CSEd, moving away from ideas reproduced by other groups that structured pedagogical proposals around competencies for the world of work or the so-called “learning to learn” (ACM, 1993).

In the early 2000s, the CSTA (Computer Science Teachers Association) was established, with researchers who also participated in the development of the ‘Computing Curricula 1991’ text, publishing in 2003 a high school education curriculum (Tucker et al., 2006). A notable point is the inclusion of the competency ‘algorithmic thinking’ [1], as in the second edition in 2006, the idea of computational thinking was introduced (Tucker et al., 2006). After some periodic curricular updates, the CSTA introduced the importance for teachers to pay attention to aspects of ‘Equity and Inclusion’, despite being presented in the BNCC (National Common Curricular Base) as a different approach, although they share the same assumptions and specialists (Brasil, 2022).

It is worth noting that concepts from the post-modern pedagogical thinking begin to be incorporated into the ‘Computational Thinking’ approach with the presence of concepts of ‘Equity and Inclusion’ [2], similar to the superficial incorporation of progressive values into traditional and technical education (Suárez, 1995; Aguiar, 2020). Suárez traces the origin of the term ‘equity’ back to neoliberal economic vocabulary, originating from the substitution of the terms equality or equal opportunities for something that implies an agreement between unequals (Suárez, 1995).

The integration of post-modern thinking in this CSEd approach stems from the understanding that there is a privilege that cuts across issues of social class, ethnicity, and gender in the construction of equal opportunities (Aguiar, 2020; Brasil 2022). According to this thinking, it is necessary to make an effort to include these young people in adapting and contributing to the social and economic transformations that may arise in the future, identifying a progressive goal in shaping the individual (Suárez, 1995; Aguiar, 2020). Furthermore, the concept of equity, central to this fourth approach (Equity and Inclusion), is related to the idea of ‘Responsible Individuality’, which attributes the realization of citizenship to the ability to understand the knowledge behind technopolitical mechanisms, which may be insufficient by belittling the existing power asymmetry and ignoring the role of social conflicts and the construction of collective subjectivities capable of interventions (Suárez, 1995).

Kafai, Proctor and Lui (2020) presents a new approach, titled “Critical Computational Thinking,” based on the critical pedagogical trend, which “emphasizes both an examination of and resistance to oppressive power structures and production-oriented media literacy, which highlights how youth agency can be acquired through the process of creating and disseminating media content” (Kafai, Proctor and Lui, 2020, p.47). The authors present a classification of practices in CSEd through three approaches: Cognitive, Situated, and Critical (Kafai, Proctor and Lui, 2020), as seen in Table 2. The critical approach has the potential to incorporate aspects grounded in critical pedagogies, such as the idea of ‘Politecnia’ [3] and Freire’s idea of ‘Praxis’, as observed in the work of Thomas, Cambraia and Zanon (2021).

Table 2: Overview of Learning Perspectives in Framing Computational Thinking (from Kafai et al., 2020)

The emergence of a critical turn in CSEd studies stems from the advances in critical and post-critical studies on critical digital culture, bringing together themes from authors from different areas close to technology, such as the cypherpunk manifesto by Hughes (1993), cyberfeminism by Plant (1997), the analysis of Californian Ideology discourses by Barbrook e Cameron (2018), the discussion on the privatization of knowledge by Swartz (2008), and studies on democracy and algorithms by Silveira (2017) [4], among other examples from critical theory. In addition to the debate from academia, other spaces for the circulation of these discourses are found in digital spaces, such as the Tecnopolítica and Tech Won’t Save Us podcasts, and physical events like cryptoparties, notably the Cryptorave [5] in the brazilian context.

Considering the contemporaneity of the approach, other forms of implementation are possible based on various works of critical pedagogy, such as the Historical-Critical Pedagogy by Saviani, 2021, the Critical-Social Pedagogy of Contents by Libâneo (2009), Freire’s Emancipatory Pedagogy, and the Critical-Reflective built from Schön (Aguiar, 2020).

Among the common aspects of the manifestation of critical pedagogy, there is the goal of building “conditions of production in which participating subjects can learn not only historically constructed activities in human ontogenesis but also learn to produce new activities in the face of the contradictions of their time” (Mattos, 2016, p. 103), as well as, according to Aguiar (2020):

“Questions the idea of the neutrality of knowledge, exploring the ideologies embedded in educational and curricular discourses. On the other hand, this perspective approaches the Progressive approach by thinking about a formation related to the life experience of students and the construction of democratic life.” (Aguiar, 2020, p. 54)

The choice of terms by which groups or forms of thought in CSEd are named, such as waves, moments, evolutions, and paradigms, as seen in the works of Neto (2002), Kaminski, Klüber & Boscarioli (2021) and Ayala & Yano (1998), may suggest that there is a sequencing of knowledge replacing previous practices. Such terms, reminiscent of the concept of paradigm proposed by Thomas Kuhn, may be inaccurate when analyzing the history of CSEd and current pedagogical trends for two main reasons: (I) recent approaches that are result of the influence and participation of researchers or practices from other areas may be mistakenly understood as better due to the contemporaneity of their thinking, even if it doesn’t represent crises in the knowledge of pioneering groups; and (II) the fact that there is no hegemony of a group of thought, important for identifying a Kuhnian paradigm, as researchers from different approaches continue to develop their field of knowledge and reproduce their practices and discourses based on their assumptions and objectives.

Educational spaces that CSEd inhabits

The use of educational software impacts the role of the teacher in the classroom, expanding or reducing their functions according to the intentionality of the tool Vosgerau; Rossari, 2017. The space for learning development and the choice of learning objectives helps to understand nuances of the CSEd approach.

The space in which education is practiced can be classified as (a) formal, defined as the “territory of schools, institutions regulated by law, certifying bodies, organized according to national guidelines” (Gohn, 2006, p. 29), (b) non-formal, which can be defined as “a set of socio-cultural learning practices and knowledge production, involving organizations/institutions, activities, means, and varied forms, as well as a multiplicity of social programs and projects” (Gohn, 2014, p. 40), and (c) informal, characterized as the space where the individual learns in an unstructured manner through everyday experiences found at home, in the neighborhood, with friends, or in the workplace (Gohn, 2006).

Another possible classification is based on the central teaching objective in which pedagogical practice is inserted, whether in the field of Computing, through the school subject of Informatics or free courses focused on computational skills and competencies or the use of tools, and in various areas, through school subjects in Mathematics, Languages, or Sciences, as well as interdisciplinary knowledge free courses involving the learning of some computational tool or skill (Carvalho; Rodriguez; Rocha, 2021; Carvalho; Rodriguez; Rocha, 2022).

There are many arguments found in scientific literature, official documents, and social discourses about the use of technologies in different curricular subjects (Aguiar, 2020), such as enriching and facilitating learning with media and situations that simulate real environments, improving performance in learning, training for the use of tools or development of computational skills in various subjects, creating new ways to engage students through more interesting approaches, and adapting students to the economic and social changes of the digital age (Chaves et al., 1983; Papert, 1993; Brasil, 1999; Maloney et al., 2004; Rodriguez, 2011; Rocha, 2014; Vosgerau; Rossari, 2017; Carvalho et al., 2019; Tarouco, 2019; Brasil, 2022; Brito; Vasconcelos; Marçal, 2022).

A series of historical factors and official documents guided the focus of CS researchers on different types of education. To contextualize CS experiences based on types of education, the classification of four CS approaches will be used, according to the particularities identified in the previous section in the works of Papert (1993), and the BNCC (Brasil, 2022): (a) instructionist, reproducing behaviorist thinking in academic approach and market perspective; (b) constructionist, reproducing constructivist thinking and inaugurated by the works of Papert and MIT Media LAB; (c) propaedeutic, based on curricular studies conducted by ACM groups, by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and contributions from nearby thought collectives, such as Wing (2006), identified in the BNCC as ‘Computational Thinking’; and (d) critical, based on the thinking of Kafai, Proctor and Lui (2020), the latter being less discussed in the section due to the contemporaneity of the approach.

Figure 1: Structure of CSEd approaches

In the last 70 years, different experiences have been carried out in non-formal education in various subjects through self-instructional pedagogical practices, often built from practices presented through instructional design. This approach was proposed from the 1960s by behaviorists, with the circulation of ideas from different fields of science, such as psychology, engineering, and mathematics. More recently, this approach has been adopted by the industry to prepare cheap labor in technology through instructional design (Dick, 1965; Seels, 1989; Brasil, 2022).

At the same time, non-formal education has also been worked on by researchers in the constructionist approach since the 1970s, both for self-learning and in organizing free courses (Papert, 1985; Kynigos, 1988). This started with the Logo tool, which enabled the emergence of derivatives like Karel and Robomind. Then, in 2007, the Scratch tool emerged, which has been continuously studied and updated to this day through an active community that learns while producing, sharing, and remixing projects (Resnick et al., 2009).

Considering efforts to introduce computers into the classroom in a context where there was still no formally defined informatics discipline, various experiments were carried out by constructionist and instructionist approaches in formal education in various subjects. This allowed for the deepening of practices guiding these approaches, the circulation of ideas among different countries, and the articulation with governments and companies in the construction of regional and national projects (Valente, 1999; Boenig-Liptsin, 2015).

In the Brazilian context, there have been several experiences that contributed to the development of constructionist and instructionist thinking in formal education spaces in various subjects until the late 1990s. Several universities served as pioneers for this development, with notable groups such as NIED/UNICAMP (Chaves et al., 1983) and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) [6].

The promulgation of the National Curricular Parameters (PCNs) and the Complementary Educational Guidelines to the National Curricular Parameters (PCNs+) between 1999 and 2002 did not structure the informatics discipline in basic education but suggested the use of technologies in formal education spaces of other subjects (Brasil, 1999). In the following years, we can observe Brazilian works in the CS area that presented pedagogical proposals in various subjects using technologies for the objectives present in PCNs and PCNs+, such as enriching learning and new ways to engage students (Pedro; Sampaio, 2005; Ficheman et al., 2006; Hoffmann; Martins; Basso, 2009).

Regarding formal education in computer science, the inclusion of this discipline in the official curriculum of several countries in the years following 1985 enabled the growth of curricular research in Computer Science in Basic Education, through learning objectives, pedagogical practices, and other pedagogical tools of local contexts (Boenig-Liptsin, 2015).

Since the 1960s, so-called ‘Computer Crises’ have been recorded several times, marked by a shortage of graduates and PhDs in Computer Science in a scenario of remaining vacancies for hiring these professionals in industry and academia, creating a debate and effort to highlight computer science in basic education, to potentially attract new generations (Gries; Walker; Young, 1989; Patterson, 2005).

In this context, efforts are being made by professional associations such as ACM and IEEE, such as the construction of public policies to include women in the field of Computing, and the founding of CSTA, with the role of developing CSEd practices and curricula, as well as collaborating with the training of teachers and youth to expand the Computing community through scientific education, as observed in the objectives of propaedeutic education (Patterson, 2005; Tucker et al., 2006; Aguiar, 2020). Other initiatives or groups dedicated to the topic emerge in the following years, including the ‘Computing in Schools’ group, from the British Computer Society, and the group acting in the Australian Department of Education, known as the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, in 2008 (Tedre; Denning, 2016).

After the initiative of the propaedeutic approach in proposing a curriculum, the instructionist and constructionist approaches also present proposals based on their assumptions. The ‘Creative Computing Guide’ text focuses on project construction with Scratch, through the constructionist approach, articulating knowledge and competencies also present in the CSTA curriculum (Brennan; Balch; Chung, 2019). Meanwhile, through the instructional approach, we find the CS Discoveries curriculum proposed by Code.org. Yet despite discussing computing topics present in curricular documents like CSTA, themes related to social impacts such as the use of data are covered superficially. These themes, potentially relevant to social transformation, are adequately in-depth in CSEd’s critical approach (Kafai, Proctor and Lui, 2020).

The promulgation of the document ‘Computing in Basic Education - Complement to BNCC’ in Brazil ensures that the subject becomes mandatory in basic education from 2023, which This document will potentially collaborate with development of curricular studies of computer science in the brazilian formal education, as well as finding ways to be adequate in different CSEd approaches (Brasil, 2022).

References

ACM, C. Pre-College Task Force Comm. of the Educ. Board of the. Acm model high school computer science curriculum. Communications of the ACM, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 36, n. 5, p. 87–90, 1993.

ACM/IEEE-CS. Computing Curricula 1991 report of the ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Curriculum Task Force. IEEE Computer Society Press, 1991.

AGUIAR, R. R. Currículo de física e prática docente: análise de uma proposta de conteúdo curricular inovador para o ensino médio. 277 p. Thesis — Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2020.

ALMEIDA, M. E. B. ProInfo: informática e formação de professores. Brasília: Ministério da Educação, Secretaria de Educação a Distância, 2000.

AYALA, G.; YANO, Y. A collaborative learning environment based on intelligent agents. Expert Systems with Applications, Elsevier, v. 14, n. 1-2, p. 129–137, 1998.

BARBROOK, R.; CAMERON, A. A ideologia californiana: uma crítica ao livre mercado nascido no Vale do Silício. Trad. Marcelo Träsel. Porto Alegre/União da Vitória: BaixaCultura/Monstro dos Mares, 2018.

BRASIL. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais–Ensino Médio (PCN). Brasília: MEC. Brasília, 1999. 109 p.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CP 2/2022. normas sobre computação na educação básica – complemento à Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC). Presidente da Comissão: Augusto Buchweitz. Relator: Ivan Cláudio Pereira Siqueira. Brasília, p. 1–34, fev. 2022. Available at: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=235511-pceb002-22&category_slug=fevereiro-2022-pdf&Itemid=30192.

BRITO, M. L.; VASCONCELOS, F. H. L.; MARÇAL, E. Integração das tecnologias da informação e comunicação no espaço escolar e sua interlocução com o projeto político pedagógico: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista Educar Mais, v. 6, p. 883–898, 2022.

BRENNAN, K.; BALCH, C.; CHUNG, M. Creative computing 3.0. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2019.

BOENIG-LIPTSIN, M. Making citizens of the information age: a comparative study of the first computer literacy programs for children in the United States, France, and the Soviet Union, 1970-1990. 389 p. Tese (Doutorado) — Paris 1, 2015.

CHAVES, E. O. C.; VALENTE, J. A.; BARANAUSKAS, M. C. C.; SILVA, H. V. R. C.; RIPPER, A. V.; VILLALOBOS, A. M. P. Projeto EDUCOM: Proposta original. Memos do NIED, v. 1, n. 1, p. 1–15, 1983.

CARVALHO, W. R. B.; RODRIGUEZ, C. L.; ROCHA, R. V. Audiojogos educacionais: um mapeamento sistemático da literatura. XXXII Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação, Sociedade Brasileira de Computação, v. 32, p. 371–380, 2021.

CARVALHO, W. R. B.; RODRIGUEZ, C. L.; ROCHA, R. V. Aprendizagem baseada em projetos no contexto do desenvolvimento de jogos: uma revisao sistemática de literatura. XXXIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação, Sociedade Brasileira de Computação, p. 267–277, 2022.

CUNHA, G. D.; RODRIGUES, C. M. C.; NUNES, D. J.; SANTOS, E. d. B.; HOLZMANN, L.; MOSCA, P. R. F.; ELLWANGER, R. J.; KORNDÖRFER, S. A.; SAMUEL, S. M. W.; RECCHI, A. M. S. Relatório: Projeto PAIPUFRGS/SINAES-4. ciclo: Avaliação institucional permanente da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: 2006-2008. Editora da UFRGS, 2010.

DICK, W. The development and current status of computer-based instruction. American Educational Research Journal, Sage Publications, v. 2, n. 1, p. 41–54, 1965.

FICHEMAN, I. K.; NOGUEIRA, A. A. M.; CABRAL, M. C.; SANTOS, B. T.; CORRÊA, A. G. D.; LOPES, R. de D.; ZUFFO, M. K. Gruta digital: um ambiente de realidade virtual imersivo itinerante para aplicações educacionais. In: Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education (Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação-SBIE). São Paulo: Sociedade Brasileira de Computação, 2006. v. 17, n. 1, p. 298–307

GARRIDO, F. A.; RÊGO, B. B. d.; MACIEL, R. S. P.; MATOS, E. S. Uma abordagem de design para MOOC: um mapeamento sistemático da articulação entre design instrucional e de interação. Revista Brasileira de Informática na Educação, v. 28, n. 1, p. 115–132, 2020.

GOHN, M. d. G. Educação não-formal, participação da sociedade civil e estruturas colegiadas nas escolas. Ensaio: avaliação e políticas públicas em educação, v. 14, n. 50, p. 27–38, 2006.

GOHN, M. d. G. Educação não formal, aprendizagens e saberes em processos participativos. Investigar em educação, v. 2, n. 1, p. 35–50, 2014.

GRIES, D.; WALKER, T. M.; YOUNG, P. The 1988 Snowbird report: A discipline matures. Communications of the ACM, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 32, n. 3, p. 294–297, 1989.

HOFFMANN, D. S.; MARTINS, E. F.; BASSO, M. V. d. A. Experiências física e lógico-matemática em espaço e forma: uma arquitetura pedagógica de uso integrado de recursos manipulativos digitais e não-digitais. Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação-SBIE, v. 20, n. 1, p. 1–10, 2009.

HUGHES, E. A cypherpunk’s manifesto. Available at: http://www.activism.net/cypherpunk/ manifesto, 1993.

KAFAI, Y.; PROCTOR, C.; LUI, D. From theory bias to theory dialogue: embracing cognitive, situated, and critical framings of computational thinking in k-12 cs education. ACM Inroads, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 11, n. 1, p. 44–53, 2020.

KYNIGOS, P. From intrinsic to non-intrinsic geometry: a study of childrens understandings in logo-based microworlds. Thesis — Institute of Education, University of London, 1988.

LIB NEO, J. C. Democratização da escola pública. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 2009. v. 23. 160 p.

MALONEY, J.; BURD, L.; KAFAI, Y.; RUSK, N.; SILVERMAN, B.; RESNICK, M. Scratch: a sneak preview [education]. In: IEEE. Proceedings. Second International Conference on Creating, Connecting and Collaborating through Computing, 2004. Kyoto, 2004. p. 104–109.

MATTOS, C. Livro didático na atividade educacional: a parte ou o todo. Enfrentamentos do ensino de física na sociedade contemporânea, LF Editorial São Paulo, p. 103–120, 2016. NETO, A. S. As cinco ondas da informática educacional. Revista Educação em Movimento./Associação de Educação Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, v. 1, n. 2, 2002.

NEVES, M.; CENTENO, C.; ORTH, M.; FRUET, F.; OTTE, J. Design educacional construtivista: O papel do design como planejamento na educação a distância. SIED: EnPED-Simpósio Internacional de Educação a Distância e Encontro de Pesquisadores em Educação a Distância, São Carlos, p. 1–12, 2012.

OLIVEIRA, D. P. d.; ARAÚJO, D. C. d.; KANASHIRO, M. M. Tecnologias, infraestruturas e redes feministas: potências no processo de ruptura com o legado colonial e androcêntrico. cadernos Pagu, SciELO Brasil, v. 59, p. 1–34, 2021.

PAPERT, S. Different visions of Logo. Computers in the Schools, Taylor & Francis, v. 2, n. 2-3, p. 3–8, 1985.

PAPERT, S. The children’s machine: Rethinking school in the age of the computer. Harper Collins, p. 242, 1993.

PATTERSON, D. A. Restoring the popularity of computer science. Communications of the ACM, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 48, n. 9, p. 25–28, 2005.

PEDRO, M. V.; SAMPAIO, F. F. PCNs e modelagem computacional: Reflexões a partir de relatos de experimentos com o software Wlinkit. Anais do Workshop de Informática na Escola, v. 11, p. 2842–2850, 2005.

PLANT, S. Zeros and ones: Digital women and the new technoculture. London: Fourth Estate, 1997. v. 4. 320 p.

RAABE, A.; COUTO, N. E. R.; BLIKSTEIN, P. Diferentes abordagens para a computação na educação básica. Computação na educação básica: fundamentos e experiências. Porto Alegre: Penso, p. 3–15, 2020.

RESNICK, M.; MALONEY, J.; MONROY-HERNÁNDEZ, A.; RUSK, N.; EASTMOND, E.; BRENNAN, K.; MILLNER, A.; ROSENBAUM, E.; SILVER, J.;

SILVERMAN, B.; KAFAI, Y. Scratch: programming for all. Communications of the ACM, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 52, n. 11, p. 60–67, 2009.

ROCHA, R. V. d. Metodologia iterativa e modelos integradores para desenvolvimento de jogos sérios de treinamento e avaliação de desempenho humano. 237 p. Thesis — Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2014.

RODRIGUEZ, C. L. A utilização de recursos audiovisuais em comunidades virtuais de aprendizagem= potencialidades e limites para comunicação e construção de conhecimentos em rede. 257 p. Thesis — Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2011.

SANTOS, G.; MAFRA, J. R. O pensamento computacional e as tecnologias da informação e comunicação: como utilizar recursos computacionais no ensino da matemática? Workshops do Congresso Brasileiro de Informática na Educação, Fortaleza, v. 7, n. 1, p. 679–688, 2018.

SAVIANI, D. Sobre a concepção de politecnia. 1987, rio de janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Politécnico da Saúde Joaquim Venâncio, p. 1–51, 1989.

SAVIANI, D. Pedagogia histórico-crítica: primeiras aproximações. 11. ed. Campinas: Autores associados, 2021. 168 p.

SWARTZ, A. Guerilla open access manifesto. Available at: https://openaccessmanifesto.wordpress.com/guerilla-open-access-manifesto/, p. 5, 2008.

SEELS, B. The instructional design movement in educational technology. Educational Technology, JSTOR, v. 29, n. 5, p. 11–15, 1989.

SILVA, I. S. F.; JUNIOR, J. D. A.; FALCÃO, T. P. Panorama sobre iniciativas para promover o pensamento computacional no ensino superior brasileiro. Anais do II Simpósio Brasileiro de Educação em Computação, Sociedade Brasileira de Computação, p. 88–98, 2022.

SILVEIRA, S. A. Tudo sobre tod@ s: Redes digitais, privacidade e venda de dados pessoais. São Paulo: Edições Sesc, 2017. 119 p.

SUÁREZ, D. O princípio educativo da nova direita: neoliberalismo, ética e escola pública. Pedagogia da exclusão: crítica ao neoliberalismo em educação. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, p. 253–270, 1995.

TAROUCO, L. M. R. Inovação pedagógica com tecnologia: mundos imersivos e agentes conversacionais. RENOTE, v. 17, n. 2, p. 92–108, 2019.

TEDRE, M.; DENNING, P. J. The long quest for computational thinking. Proceedings of the 16th Koli Calling international conference on computing education research, p. 120–129, 2016.

TELES, F. P. O brincar na educação infantil com base em atividades sociais, por um currículo não encapsulado. 216 p. Thesis — Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018.

THOMAS, R.; CAMBRAIA, A. C.; ZANON, L. B. Formação integrada na educação profissional e tecnológica: Pensamento computacional e crítico por meio do ensino de programação. Revista Tecnologias Educacionais em Rede (ReTER), v. 2, n. 4, p. 1–15, 2021.

TUCKER, A.; DEEK, F.; JONES, J.; MCCOWAN, D.; STEPHENSON, C.; VERNO, A. A model curriculum for k–12 computer science. Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), New York, 2006.

VALENTE, J. A. Questão do software: parâmetros para o desenvolvimento de software educativo. Memos do NIED, Campinas, v. 5, n. 24, p. 1–14, 1989.

VOSGERAU, D. S. R.; ROSSARI, M. Princípios orientadores da integração das tecnologias digitais ao projeto político-pedagógico. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, v. 12, n. 2, p. 1020–1036, 2017.

WING, J. M. Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, ACM New York, NY, USA, v. 49, n. 3, p. 33–35, 2006.

[1] Silva, Junior and Falcão (2022) identifies algorithmic thinking as one of the pillars of Computational Thinking, along with decomposition, pattern recognition, and abstraction. A definition of thinking is “a structuring to design machine instructions to produce a computational solution to solve problems”

[2] Standards for CS Teachers - Computer Science Teachers Association. Available at: https://csteachers.org/teacherstandards/. Accessed on August 23, 2023.

[3] According to Saviani (1989), ‘Politecnia’ is not about training a worker to perform a specific task but developing a multilateral development, covering all angles of modern productive practice as it masters the principles underlying modern work organization, based on scientific principles.

[4] Tecnopolítica Podcast. Available at:https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDy46jf2mcg8xy SzrqV5pxw . Accessed on 30/07/2023.

[5] Cryptorave revolves around the concepts of freedom and privacy in the context of technology, held “annually since 2014 and organized voluntarily and collaboratively by activist collectives based in the State of São Paulo. It is inspired by Cryptoparty, a global and decentralized initiative for holding events that discuss surveillance and network security and introduce basic cryptography concepts’’ (Oliveira, Araújo and Kanashiro, 2021).

[6] Especially the Laboratory of Cognitive Studies (LEC)/UFRGS, the Data Processing Center (CPD/UFRGS), and the Interdisciplinary Center for New Education Technologies (CINTED/UFRGS) (Cunha et al., 2010).

Publicado por Walter Bolitto Carvalho

bolitto.walter(arroba)gmail.com

(C:)

(C:) /curriculo

/curriculo Leia-me

Leia-me